Analgesics/NSAIDS

Acetaminophen is an effective pain relief medication. It is usually preferred over anti-inflammatory medication, at least initially. Anti-inflammatory medication (Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 'NSAIDS') may accelerate the degenerative process and/or lead to more severe joint destruction at time of surgery. Side effects of NSAIDS are numerous. This should be carefully discussed with the family doctor, prior to starting treatment. These medications do not 'cure' arthritis, they provide relief from some of the symptoms, most notably pain. If tolerated, this type of treatment is usually among the first steps in active treatment of osteoarthritis. In general, it would be preferable to adjust the intensity of exercise to maintain fitness, while minimizing NSAID use. Excessive exercise, facilitated by ongoing NSAID use, holds the real risk of accelerating the arthritic process. |

|

|

Injections: cortisone/ visco-supplementation

Cortisone-like medication (methylprednisolone, triamcinolone, betamethasone) may provide short-term pain relief (3-6 months). Risk of infection is present with each injection. This has a limited role in the treatment of osteoarthritis, and may be more useful in inflammatory arthritis. This type of treatment does not 'cure' arthritis, it brings relief of symptoms only.

Visco-supplementation ( hyaluronic acid derivatives/analogues, Synvisc, others): limited information. Most, if not all, products in this category are marketed as 'medical devices' rather than as medication. Typically, a series of 3 injections, one week apart, is administered. Some of the newer formulations claim higher and more sustained levels of hyaluronic acid in the joint, even with just one single injection. It appears that approximately 80% of patients may have clinical benefit, lasting on average 8 months, with a wide variability. It may be that this type of device works better in isolated, relatively early medial compartment OA. Its effectiveness in treatment of patello-femoral arthritis may be less than stated above as an average response. Some products regularly produce excessive swelling/pain/redness, which is difficult to differentiate from an infection, and may lead to antibiotic treatment or even surgical lavage of the knee joint. Of course, the risk of a real infection is present with each injection. In my view, no convincing evidence is present to support the claim that visco-supplementation leads to cartilage restoration. In my practice, this treatment modality only has a very limited role.

|

|

|

Topical: Diclofenac in DMSO

A topically applied liquid, consisting out of an non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (diclofenac) in a skin-penetrating carrier (DMSO). Limited clinical information is available. Most likely, it will be effective to some degree in bringing pain relief. It is unclear if this is better than after taking diclofenac by mouth or as a suppository. Furthermore, it is expected that the side-effects of NSAID treatment are reduced by local application, this remains to be established. |

|

|

Supplements; glucosamine/ chondroitin/ MSM

Benefit unclear. After well over 2 decades of use, the benefits of these supplements have still not been clearly demonstrated. Undoubtedly, some people feel better when taking these products: it is unclear if this represents an anti-inflammatory effect or placebo effect. Little evidence is present to suggest a meaningful cartilage 'protective' or even 'restorative' effect, which was the original 'claim to fame'. A recent study at the University of British Columbia demonstrated NO benefit. |

|

|

Magnets/ heat/ cold/ other physical

Physical interventions are most effective when active inflammation is present, either acute or chronic. This type of treatment is usually guided by a physiotherapist, and may facilitate ongoing conditioning. The effect of magnets is poorly understood. |

|

|

Conditioning & Exercise

Conditioning in the presence of arthritis of the knee can be difficult. Joint pain interferes with activity, and makes it more difficult to achieve adequate energy expenditure for weight control and to achieve adequate strengthening.

However, losing muscle tone, range of motion and gaining weight will exacerbate the effect of the arthritis. Articular cartilage needs use of the joint to maintain its health. Usually, some form of exercise can be tolerated well into the arthritic process, incl. swimming, deep-water walking/running, cycling, stepping machines, walking, and moderate weight training. It is usually best to design a program based on personal preference (an enjoyable exercise routine has a higher chance of success), with input from physicians, physiotherapy and/or a personal trainer. The principle should be to maximize exercise load without causing active inflammation or pain. 'You can do almost anything, as long as it does not cause pain' and 'listen to your body'. The saying 'no pain, no gain' does NOT apply in conditioning of joints with arthritis.

Aim for a body mass index less than 30, perhaps closer to 25. Being close to your ideal body weight avoids over-loading the weight bearing joints. Even in the presence of some arthritis, pain and diminished functional ability are less pronounced near ideal body weight. Furthermore, avoiding ongoing 'over-loading' is important to possibly diminish the rate of progression.

In order to not encounter increased surgical risks, I prefer patients to have a body mass index less than 35 at the time of joint replacement surgery.

Conditioning and quadriceps strengthening is the mainstay of treatment of patello-femoral symptoms. Surgical treatment of patello-femoral arthritis remains problematic. Achieving optimal conditioning of the quadriceps muscle can alleviate significantly the pain and loss of function related to patello-femoral arthritis. It may be that help from physiotherapy is required to achive significant quads strengthening without undue aggravation or discomfort.

|

|

|

Unloading bracing medial

For medial compartment osteoarthrosis, unloading bracing can bring significant, immediate pain relief. This may facilitate ongoing conditioning. Furthermore, there is some evidence to suggest that consistent bracing for relatively early medial compartment ostearthrosis may slow down the rate of progression of the degenerative process.

Typically, these braces are most effective when they are custom-fitted to the involved leg. A brace is most readily accepted when only one knee is involved. However, bracing of both knees is possible. In my experience, a double hinged brace is more effective and less bulky than a single-hinged brace. Bracing can avoid or delay the need for surgery, and is an important treatment modality for uni-compartmental arthrosis of the knees.

Generally, 2 types of braces can be distinguished: single-hinged or double-hinged. In my practice, double-hinged braces have been much more successful in the treatment of uni-compartmental osteoarthrosis than double-hinged braces. It is more feasible to obtain meaningful unloading with a double hinged brace. The double hinged brace tends to be less bulky and is easier fitted under under trousers. In warm weather, many people find the closed nature of the single- hinged brace unpleasant.

Double-hinged brace

Single Hinged Brace:

|

|

|

Unloading bracing lateral

For lateral compartment osteoarthrosis, unloading bracing can bring significant, immediate pain relief. This may facilitate ongoing conditioning. Furthermore, there is some evidence to suggest that consistent bracing for relatively early ostearthrosis may slow down the rate of progression of the degenerative process. This is better documented for medial compartment osteoarthrosis. In my experience, bracing for lateral compartment osteoarthrosis is not as reliable as bracing for medial compartment osteoarthrosis.

Typically, these braces are most effective when they are custom-fitted to the involved leg. A brace is most readily accepted when only one knee is involved. However, bracing of both knees is possible. In my experience, a double hinged brace is more effective and less bulky than a single-hinged brace. Bracing can avoid or delay the need for surgery, and is an important treatment modality for uni-compartmental arthrosis of the knees.

Generally, 2 types of braces can be distinguished: single-hinged or double-hinged. In my practice, double-hinged braces have been much more successful in the treatment of uni-compartmental osteoarthrosis than double-hinged braces. It is more feasible to obtain meaningful unloading with a double hinged brace. The double hinged brace tends to be less bulky and is easier fitted under under trousers. In warm weather, many people find the closed nature of the single- hinged brace unpleasant.

Double-hinged brace

Single Hinged Brace:

|

|

|

Patellar bracing

For patello-femoral osteoarthrosis, predominantly involving either the lateral or medial compartment, a patellar-tracking-orthosis may bring some relief, by unloading the most affected side of the patella. Its main function is to allow progressive conditioning and quadriceps strengthening, without excessive exacerbation of symptoms during the conditioning process. In order to meaningfully affect the tracking of the patella, these braces have to be somewhat bulky. This may be cumbersome with full knee flexion and in warm weather.

|

|

|

High tibial osteotomy, valgus producing, closing wedge

For medial compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee, closing wedge osteotomy of the tibia, just below the joint surface, is a well-established technique. Alignment of the leg is altered from a 'bow-legged' or varus alignment, aiming for a 'knocked-knee' or accentuated valgus position. The weightbearing forces will preferentially be directed through the preserved lateral compartment.

Pre-requisites for this procedure are complete preservation of the lateral compartment, approximately 25-50% preservation of the medial joint space, intact ligaments. It is quite an involved procedure: the tibia (shinbone) is cut across twice with a saw, after which a wedge of bone is removed. This space is closed by bringing the leg over into the desired position. This is then maintained by a fixation device, usually staples or a plate. The bone then needs to heal, just like a fracture, which takes usually 6-8 weeks. Complications can occur, these can be serious.

Concerns regarding closing wedge osteotomy include the following:

- The accentuated valgus position is not always well tolerated, both from a functional and from a cosmetic perspective.

- The lateral compartment is relatively overloaded (full weight through approx 50% of the original weightbearing surface), and is subject to further wear, often within 5-10 years. If the knee becomes painful because of the development of significant arthritis in the lateral compartment, total knee replacement would be the next step.

- Total knee replacement after high tibial osteotomy, closing wedge, if/when necessary, has proven to be more difficult than a primary total knee replacement, and the results are not as good. The outcome is more like that of a revision of a total knee replacement to another total knee replacement. This is an important consideration when deciding between a unicompartmental (partial) knee replacement and a closing wedge osteotomy in the treatment of medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee:

- a) partial knee replacement has a 90-95% probability of good function at 10 years. If conversion to a total knee replacement is needed, this is more involved than a primary knee replacement, but with results very similar to a primary total knee replacement.

- b) closing wedge osteotomy has a 40-50% probability of good function at 5-8 years. If conversion to total knee replacement is needed, this more like a revision total knee operation, with results inferior to a primary knee replacement.

In my practice, closing wedge osteotomy has not been used in the last 5 years. Osteotomy may be a reasonable option for a patient who cannot accept the restrictions in activity after a unicompartmental knee replacement.

|

|

|

High tibial osteotomy, valgus producing, opening wedge

As in closing wedge osteotomy, alignment of the leg is altered from a 'bow-legged' or varus alignment, aiming for a 'knocked-knee' or accentuated valgus position. The weightbearing forces will preferentially be directed through the preserved lateral compartment. Pre-requisites for this procedure are complete preservation of the lateral compartment, approximately 25-50% preservation of the medial joint space, intact ligaments. It is quite an involved procedure: the tibia (shinbone) is cut across once with a saw, after which the bone is carefully wedged open, until the desired position has been obtained. The space created is maintained by a fixation device, usually a special plate with a buttress, or a block of bone. The bone then needs to heal, just like a fracture, which takes usually 6-8 weeks. Complications can occur, these can be serious.

This technique has several potential advantages over the closing wedge technique: because of the gradual opening, with the possibility of 'fine-tuning', a more precise change in alignment can be achieved. It may be that this will lead to a more physiological loading of the lateral compartment, perhaps leading to less wear. Possibly, opening wedge osteotomy may bring relief of pain for a longer period of time than closing wedge osteomy, with possibly easier revision to total knee replacement when required. This has not been firmly established. Firm data are scarce regarding the outcome after using this technique.

In my practice, I have not used this technique in the last 5 years. However, the technique is interesting, and may find a firm place in the treatment of osteoarthritis, either by itself, or as an adjunct to a biological treatment that requires some protection from the weight bearing forces.

Osteotomy may be reasonable for the patient who cannot accept the restrictions in activity level associated with unicompartmental knee replacement.

|

|

|

High tibial osteotomy, varus producing, closing wedge

For medial compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee, closing wedge osteotomy of the tibia, just below the joint surface, is a well-established technique. Alignment of the leg is altered from a 'bow-legged' or varus alignment, aiming for a 'knocked-knee' or accentuated valgus position. The weightbearing forces will preferentially be directed through the preserved lateral compartment. The opposite technique can be used for lateral compartment osteoarthrosis. This is not commonly used, mainly because of inability to obtain sufficient correction. Very limited information is available on the results of this technique. I have not used this in my practice in the last 5 years.

Osteotomy may be reasonable for the patient who cannot accept the restrictions in activity level associated with unicompartmental knee replacement.

|

|

|

High tibial osteotomy, varus producing, opening wedge

Opening wedge osteotomy is a treatment modality not uncommonly used for the treatment of medial compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee. A similar technique can be used for lateral compartment osteoarthrosis. Currently, not much information is available regarding the outcome of this approach. I have not used this technique in my practice over the last 5 years.

Osteotomy may be reasonable for the patient who cannot accept the restrictions in activity level associated with unicompartmental knee replacement.

|

|

|

Distal femoral osteotomy, varus producing, closing wedge

For lateral compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee, tibial osteotomies to change the alignment from valgus ('knocked-knee') into varus ('bow-legged') alignment may not have enough corrective ability. Cutting the femur just above the knee is a very powerful corrective technique. Because of the magnitude of the procedure and uncertainty about outcomes, this technique is not utilized widely.

Osteotomy may be reasonable for the patient who cannot accept the restrictions in activity level associated with unicompartmental knee replacement.

|

|

|

Distal femoral osteotomy, varus producing, opening wedge

For lateral compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee, tibial osteotomies to change the alignment from valgus ('knocked-knee') into varus ('bow-legged') alignment may not have enough corrective ability. Cutting the femur just above the knee is a very powerful corrective technique. Because of the magnitude of the procedure and uncertainty about outcomes, this technique is not utilized widely. Using an opening wedge technique will allow gentle, gradual correction, with precise fine tuning to achieve the desired position. It may prove to be an effective technique in the treatment of lateral compartment osteoarthritis.

Osteotomy may be reasonable for the patient who cannot accept the restrictions in activity level associated with unicompartmental knee replacement.

|

|

|

UKA medial, mobile bearing

Medial compartmental knee replacement with a mobile, non-restrained bearing prosthesis (Oxford knee) is my preferred method of dealing with end-stage, bone-on-bone predominantly medial compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee. This because of the well-documented favorable immediate and long term outcome. In this operation, only the 'worn-out' part of the knee is replaced, the remainder of the knee is left alone. Prerequisites for a good long term outcome are preservation of the lateral compartment, as demonstrated on X-ray stress views, as well as integrity of the cruciate ligaments, demonstrated through MRI or arthroscopy. Under these circumstances, 90-95% of these prostheses are expected to still function well at 10 and 15 years. This is similar to the outcome after total knee replacement. For the 5-10% of patients who have required a revision of the initial knee replacement, either unicompartmental or total, by 10 years, a revision from unicompartmental knee replacement to total knee replacement is easier and will have a better long-term outcome than a revision from total to total knee replacement. Starting with a medial unicompartmental knee replacement under well-defined conditions, is expected to yield a longterm outcome similar to total knee replacement, with less surgical risk and more options for revision than after providing immediate total knee replacement, i.e. 'don't burn the bridges until you have to'.

New developments include the availability of a non-cemented, hydroxy-apatite coated femoral component, currently (Sepember 2004) available through special permit from the Health Protection Branch in Canada. A non-cemented tibial component is expected relatively soon.

Although a unicompartmental knee replacement is less involved than a total knee replacement, it is a replacement operation nonetheless, with significant risks and possible complications (see 'consent UKA'). This option should not be considered lightly. Rather, it should be seen as a last resort, after exhaustion of other treatment modalities, incl analgesics/NSAIDS, conditioning and bracing.

|

|

|

UKA medial, fixed bearing

Medial compartmental knee replacement with a fixed bearing prosthesis (such as the Miller-Gallante) is a good method of dealing with end-stage, bone-on-bone predominantly medial compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee. This because of the documented favorable immediate and long term outcome. In this operation, only the 'worn-out' part of the knee is replaced, the remainder of the knee is left alone. Prerequisites for a good long term outcome are preservation of the lateral compartment, as demonstrated on X-ray stress views. The importance of cruciate ligaments integrity may be less for this type of prosthesis than for the mobile bearing unicompartmental knee replacement. 90-95% of these prostheses are expected to still function well at 10 years. The number of patients reported on in long-term follow-up studies is less than for the mobile bearing knee replacement. The results at 10 years are similar to the outcome after total knee replacement. For the 5-10% of patients who have required a revision of the initial knee replacement, either unicompartmental or total, by 10 years, a revision from unicompartmental knee replacement to total knee replacement is easier and will have a better long-term outcome than a revision from total to total knee replacement. Starting with a medial unicompartmental knee replacement under well-defined conditions, is expected to yield a longterm outcome similar to total knee replacement, with less surgical risk and more options for revision than after providing immediate total knee replacement, i.e. 'don't burn the bridges until you have to'.

Although a unicompartmental knee replacement is less involved than a total knee replacement, it is a replacement operation nonetheless, with significant risks and possible complications (see 'consent UKA'). This option should not be considered lightly. Rather, it should be seen as a last resort, after exhaustion of other treatment modalities, incl analgesics/NSAIDS, conditioning and bracing.

|

|

|

UKA lateral, mobile bearing

The current design of the most commonly used unicompartmental knee replacement (Oxford knee) has a bearing dislocation rate possibly as high as 10%. Because of this, a mobile bearing partial knee replacement is currently not recommended for lateral compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee. |

|

|

UKA lateral fixed bearing

Lateral compartmental knee replacement with a fixed bearing prosthesis (such as the Miller-Gallante) is a good method of dealing with end-stage, bone-on-bone predominantly lateral compartment osteoarthrosis of the knee. This because of the documented favorable immediate and long term outcome. In this operation, only the 'worn-out' part of the knee is replaced, the remainder of the knee is left alone. Prerequisites for a good long term outcome are preservation of the medial compartment, as demonstrated on X-ray stress views. The importance of cruciate ligaments integrity is uncertain. 90-95% of these prostheses are expected to still function well at 10 years. The number of patients reported on in long-term follow-up studies is less than for medial compartmental knee replacement. The 10 years results appear similar to the outcome after total knee replacement. For the 5-10% of patients who have required a revision of the initial knee replacement, either unicompartmental or total, by 10 years, a revision from unicompartmental knee replacement to total knee replacement is easier and will have a better long-term outcome than a revision from total to total knee replacement. Starting with a lateral unicompartmental knee replacement under well-defined conditions, may yield a longterm outcome similar to total knee replacement, with less surgical risk and more options for revision than after providing immediate total knee replacement, i.e. 'don't burn the bridges until you have to'.

Although a unicompartmental knee replacement is less involved than a total knee replacement, it is a replacement operation nonetheless, with significant risks and possible complications (see 'consent UKA'). This option should not be considered lightly. Rather, it should be seen as a last resort, after exhaustion of other treatment modalities, incl analgesics/NSAIDS, conditioning and bracing.

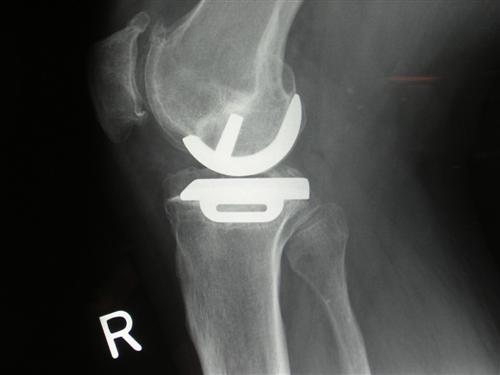

Pre-operative pictures:

Lateral compartment osteoarthritis: varus stress view

Lateral compartment osteoarthritis: valgus stress view

Lateral compartment osteoarthrosis: fixed bearing unicompartmental knee replacement (Miller-Galante)

|

|

|

TKA

Total knee replacement has been the standard procedure to deal surgically with severe osteoarthritis of the knee. This involves replacement of the joint surfaces of the femur (thighbone) and the tibia (shinbone). Replacing the joint surface of the patella (knee cap) is optional, and a point of ongoing discussion.

Results of this procedure have been very good with 90-95% of these devices still functioning well at 10 years. However, it is a fairly involved procedure. Complications occur, which can be very serious (see consent TKA).

Newer developments include surgery through smaller incisions, with less soft tissue disruption. It is not clear if this will decrease the frequency and/or severity of the various recognized complications.

It is important to realize that the outcome of this procedure can vary significantly between individuals: it has been reported that 90% of patients have a good or excellent result, while 10% of patients will have a fair or poor result. Patients who have a worker's compensation claim related to this procedure, may only have a 35-40% likelihood of having a good/excellent result. These are sobering statistics, and need to be well understood by all involved.

In situations where predominantly one weightbearing compartment is involved, uni-compartmental (partial) knee replacement may be an alternative to total knee replacement. Under the right circumstances these devices are expected to have a similar survival at 10 years as a total knee replacement, i.e. 90-95%. Given the similar outcome, the following 2 considerations need to be carefully considered:

Unicompartmental knee replacement may have a lower infection risk than total knee replacement (1-2% for total knee vs. 0.5-1% for uni-knee). This is a very important statistic: infection is a devastating complication, often leading to prolonged treatment, with multiple extensive operations, with a success rate of 90%. An infected knee replacement that cannot be cured, usually ends up as an amputation, or possibly a knee fusion (stiff, straight leg)

Furthermore, 90-95% success at 10 years means that 5-10% of these prostheses are taken out within the first 10 years, usually due to loosening or wear of the components. These are then replaced with a new device, almost always a total knee replacement. Revising a unicompartmental knee to a total knee is less of an operation with better results, compared to revising a total knee replacement to another total knee replacement.

Total knee replacements are typically designed to accommodate activities such as walking, even brisk walking, cycling, golf, swimming. Jogging will lead to premature failure, and is strongly discouraged. Return to doubles' tennis is possible for some, it is not quite clear if this activity level increases the risk of early device failure.

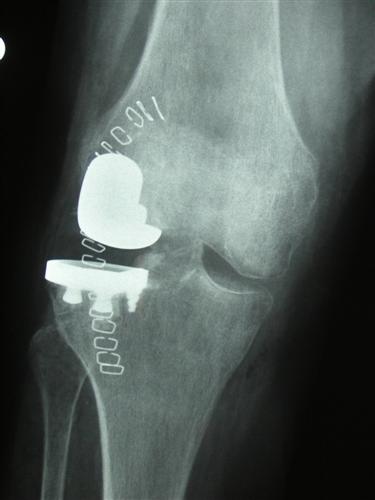

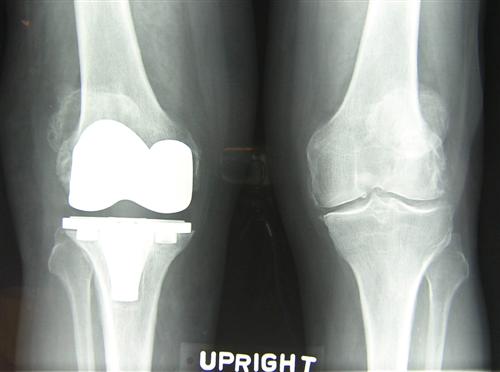

Example 1: Pre-operative -- severe arthritis with deformity

After Total Knee Replacement, non-cemented:

2/ Example 2: Unicompartmental knee replacement (Oxford-cemented) and Total Knee replacement (cemented)

Example 3: Preoperative.

After total knee replacement (TKR):

|

|

|

Arthroscopy for osteoarthritis with mechanical symptoms.

If the symptoms related to arthritis of the knee include prominent locking, catching or giving way of the knee, arthroscopy of the knee may be helpful as a temporizing measure. Flaps of unstable joint surface cartilage, unstable tears of the meniscal cartilage (shock absorbing cartilage), loose debris and rough joint surfaces may lead to 'seizing' of the knee joint. As a reflex protective response, the body may instruct the muscles in front of the thigh ('quadriceps') to relax instantaneously, to diminish the pain. This may lead to falls or 'near-falls', a sensation of 'giving way' without necessarily having an unstable knee.

If these symptoms are more of a problem than an ongoing, constant ache, that gradually increases or decreases related to the activity level, than 'cleaning out' the knee joint through arthroscopic evaluation, debridement (smoothing, removal of loose debris), and dealing with meniscal damage as indicated, may bring significant improvement, which may be sustained for a significant amount of time, possibly a few years. This will vary considerably, mainly due to the variable progression of the ache associated with the arthritis. In other words, one can remove the debris and smooth the joint surfaces, so that the 'bearing' runs a little better, but the surfaces are not as smooth and shiny as they once were, and further wear and tear is inevitable.

|

|

|

Arthroscopy for osteoarthritis without mechanical symptoms

If the symptoms related to arthritis of the knee mainly consist out of a prominent ache, related to activity level, without significant locking or catching, arthroscopy of the knee may not be very helpful. 'Cleaning out' the knee may bring some relief of pain, to a markedly varied degree, for a short period of time, usually measured in months rather than years. Similar results may be obtainable after 'lavage' of the knee: flushing the knee with a sterile solution may bring some pain relief by itself. It may be that the effect of both of these procedures is a 'placebo' effect to some degree.

It may be valuable to perform arthroscopy under these circumstances for other reasons, such as assessment of the joint surface and the cruciate ligaments if unicompartmental (partial) knee replacement or osteotomy (re-alignment surgery) is considered. An alternative to this may be MRI examination, as a non-invasive imaging modality.

|

|

|

Lateral release

For osteoarthrosis of the patellofemoral joint, particularly with bone-on-bone contact laterally, lateral release of the patella (kneecap) MAY bring some relief of pain. This involves dividing the tissues tethering the knee cap through a small incision or arthroscopically. The underlying rationale is that decreasing the pressure on the worn joint surfaces will lead to less pain. Although this is a rather small operation to perform, significant difficulty can be encountered afterward, related to bleeding or leakage of joint fluid. Pain relief is almost always only moderate at best, and often very little improvement is obtained.

In my practice, the use of this procedure in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the patello-femoral joint is quite limited. It is used from time to time for debilitating patello-femoral osteoarthrosis as a first step, in an attempt to bring some pain relief and improvement in function, without resorting to a large operation.

|

|

|

Patellectomy

Removing the kneecap (patella) as treatment for patellofemoral osteoarthrosis can be reasonably effective in providing pain relief. However, in many patients this will lead to significant weakness in straightening the leg, particularly the last 15-30 degrees. Because of this functional limitation, this operation is currently only rarely performed for osteoarthrosis. |

|

|

Patellofemoral replacement

Replacing the patello-femoral joint surfaces, by providing a smooth prosthetic component to the joint surface of the patella in isolation or coupled with resurfacing of the femoral groove surface, has been tried in various manners over the years. This has not met with great success on a consistent basis. Efforts in this direction continue. Although prostheses for isolated patello-femoral replacement are available, the results of this approach have not been firmly established yet. |

|

|

Oblique tibial tubercle osteotomy

When isolated patello-femoral osteoarthrosis involves mainly the lateral facet of the patella, and is associated with lateral tethering of the patella, leading to tilt and/or subluxation, an oblique osteotomy of the tibial tubercle ('Fulkerson osteotomy') can be considered. This involves an oblique saw cut through the tibia, to move the attachment of the patellar tendon forward (anteriorly) and inward (medially). The rationale for this procedure is to re-align the patella into the middle of the femoral groove, while diminishing the forces going through the joint surfaces by moving the tendon attachment forward.

This is a fairly involved procedure. Afterward, the cut surfaces have to heal together again, usually in 6-8 weeks. Limited weightbearing during this period may be necessary for protection of the repair.

Some improvement can be expected reasonably consistently, but pain relief may very well remain incomplete.

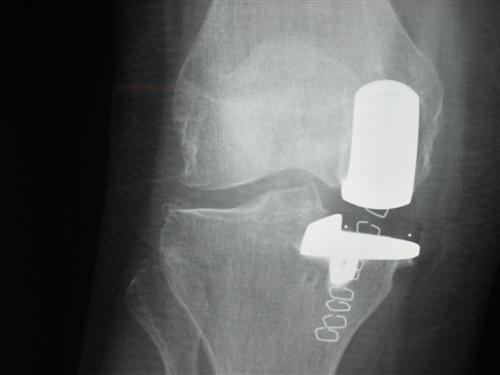

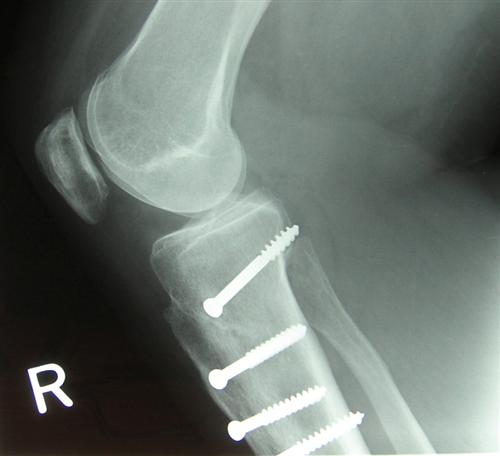

Post-operative X-ray after oblique tibial tubercle osteotomy.

|

|

|

Anteriorizing tibial tubercle osteotomy

Symptoms due to osteoarthrosis of the patello-femoral joint may improve after anteriorizing tibial tubercle osteotomy ('Macquet procedure'). This procedure reduces the magnitude of the forces through the joint surfaces of the patella (knee cap) and the corresponding groove on the femur (thighbone) by moving the attachment of the patellar tendon anteriorly (forward). This is an extensive procedure, with a long (10-15 cm) saw cut of the tibial tubercle, which is 'wedged' open to the desired position. This position is then maintained, usually by a block of the patient's own bone, harvested from the iliac crest ('hip bone' or 'pelvic bone'), kept in place by a screw.

This is a fairly involved procedure, with the potential for significant complications. This procedure should be considered only after all conservative, non-operative measures have truly been exhausted.

Post-operative X-ray after anteriorizing tibial tubercle osteotomy.

|

|

|

Interposition arthroplasty

Interposition arthroplasty consists of insertion of a smooth spacer into the joint, to separate the worn out joint surfaces and to provide a smooth surface for motion. This type of procedure, using a metallic spacer, was used in the 1950's and 60's, prior to the advent of modern knee replacement procedures.

More recently, a modern design metallic spacer has received renewed attention as a treatment option for medial compartment osteoarthrosis. Very little information is available about the outcome of this procedure. It appears that pain relief is not always complete or satisfactory, possibly due to the stiffness of the metal implant (metal is much stiffer than bone). Dislocation of the implant has been an issue as well, it may be that design changes may remedy this.

Other materials are being considered for interpositional arthroplasty, utilizing synthetic materials that provide a smooth gliding surface and have the ability to function as a shock absorber, to hopefully provide pain relief without the need for removal of bone for insertion of metallic implants.

|

|

|

Biological resurfacing

Resurfacing of damaged joint surfaces with cartilage is possible for well defined local lesions, of reasonable size. One technique utilizes 'plugs' of bone with cartilage covering, taken from another area. This may jeopardize the function of the donor area ('robbing Peter to feed Paul'). Alternatively, a small amount of joint cartilage can be harvested, to allow culture of cartilage cells in the laboratory. These are then implanted during a second procedure. This method can be utilized for small isolated lesions only.

Typically, neither of these procedures is utilized in primary osteoarthrosis. More often, these are considered for isolated lesions, such as found after injury or focal cartilage/bone disorders, such as osteochondrosis dissecans or perhaps avascular necrosis.

|

|

|

Knee fusion

The pain associated with osteoarthrosis can be alleviated reliably by eliminating motion. Permanent, definitive elimination of motion can be achieved by fusing the knee. The femur (thigh bone) becomes one with the tibia ('shin bone'), leading to a stiff straight leg. Once the fusion is complete, good ability to weight bear can be expected. In the long run (measured in decades, rather than in years), excessive wear of the hip and/or lower back may become problematic. In more recent years, fused knees have been converted to total knee replacements, to restore motion. Clearly, the atrophied (wasted) thigh muscles will need time to be partially rehabilitated.

The inability to bend the knee interferes with many situations, such as getting in and out of a car, sitting with limited leg space, etc, and is currently not widely utilized because of these limitations in function. It does however allow a high activity level, including sports. On occasion, this may be considered a reasonable option in a young (20's-30's) patient, for whom the restrictions associated with the use of replacement procedures are unacceptable. High intensity sporting activity will lead to premature wear of prosthetic implants.

I have not used this option in my practice in the last 5 years.

|

|

|

Homeopathic

You may also consider homeopathic care.

|